Are Mothers "Allowed" To Be Creative?

The real, messy, complicated journey of becoming (or choosing not to become) a mother.

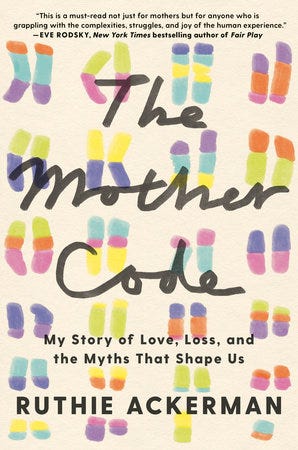

This Mother’s Day, we wanted to go beyond the greeting cards and brunch plans—and talk about the real, messy, complicated journey of becoming (or choosing not to become) a mother. We sat down with Ruthie Ackerman, author of The Mother Code, a powerful memoir that asks the big questions: What does it really mean to mother? And who gets to decide?

Her story starts in a place a lot of us might recognize—with a firm “no thanks” to motherhood, shaped by all the narrow versions of it we see in movies, media, and our own families. But over time, that “no” turned into curiosity, and then into a deeper reckoning with identity, legacy, and desire. Ackerman opens up about challenging the either/or story we’re told—that we can be mothers or be ourselves—and what it might look like to write a new narrative. One that leaves room for ambition, creativity, humanity… and a whole lot less guilt.

Briefly describe your journey to motherhood.

My journey to motherhood went from “hell no” (why would I do that to myself?) to curiosity to a full-on investigation/reckoning. The “hell no” phase was spurred by all the images of motherhood I saw around me: the selfless, saccharine mothers we see in movies and on TV and the even more insidious messages we get that women have to give up their identities to become mothers. Mothering as an either/or – either my child or myself – never sat right with me.

The curiosity phase was more of a spark, a question: Who’s to say mothering has to be this way?

And then the investigation/reckoning phase where I began to dig into the family mythologies I had grown up with my whole life and realized that some of that lore simply wasn’t true (or may not have been true) and yet I was basing my personal decisions on whether to mother on these falsehoods or half truths.

What were some of the factors that led you to decide to freeze your eggs? What kind of medical guidance were you given, and what were the conversations with your friends and family like?

When I froze my eggs in 2013 the American Society of Reproductive Medicine had just removed the experimental label from the procedure so I didn’t know of many women who had done it yet. There had only been 500 births worldwide from frozen eggs so I truly felt like a guinea pig. The only reason I decided to freeze my eggs in the first place was because my close friend who is 5 years older than me was struggling to get pregnant at the time and I thought, “What if I change my mind? What if some day I decide I do want a baby?”

I was given no medical guidance. There was no informed consent conversation that I can remember. Now I have looked at the fine print on the contracts I signed but at the time no one went through the ins and outs of egg freezing with me. And I didn’t tell my family or friends because I was filled with shame that I had done something wrong to be in this situation in the first place. I didn’t know anyone else who’s husband didn’t want to have kids with them. I believed something was wrong with me to make him not want to have children. It was a total mindfuck.

How did you decide to have a baby? Did you “know,” did it feel more like a rational decision, or some combination?

The language of choice (and decision) in this context has always baffled me. As humans we make choices without really knowing what those choices are. We put one foot in front of the other day by day and only by looking back can we see what those choices or decisions were. I didn’t decide to have a baby. The question of whether I should have a baby haunted me for so long that my first husband Evan divorced me over it (he didn’t want a baby under any circumstances). Even after my divorce my therapist asked me how badly I wanted a baby on a scale of 0-100 and I said 55%. I wanted a baby a teensy bit more than I didn’t want a baby. There was never a “hell yes” moment. I never knew. Part of that was fear of passing down my half-brother’s genetic mutation(s) and the mental illness that I knew ran in my family. And some of us won’t ever be all-in on parenthood. Yet the message we get from society is that we should only have kids if we are all-in. Again: who says? The decision to have a kid never felt rational. All I knew was that the kid question kept me up at night and eventually I woke up and knew my phantom child’s name. I guess that’s a kind of knowing, but as a journalist (and a believer in science) I was looking for irrefutable facts. I wanted to know beyond a shadow of a doubt whether I should have a baby – and no one and nothing could tell me that.

How do you want to see the cultural conversation around mothering change?

I could write a whole book on just this question! Let’s start with this: I want to debunk the idea that women need to give up their own dreams and desires to become mothers. We can mother and be artists. We can mother and be scientists. We can mother and be all the other things we want to be. The problem comes when women are bombarded with the voices of what everyone else wants for–and from–us, so much so that we can no longer know what we want for ourselves. We are told we have to give up everything to become mothers, and then we’re shown images of other women doing just that, so we believe that’s the only way to do motherhood “right.” I want to question a society that tells us we can’t be mothers and make masterpieces too. That we have to be selfless and give all of our energy to our children to the detriment of our own identities. There’s also this: we all don’t need to be mothers! That’s ok too. We lose our humanity when we all go after the same things on the same timelines. That’s what robots do!

We don’t see a lot of role models for what a good life can look like outside of marriage and motherhood. And I want to change that. I want women to be self-actualized, to figure out what they want to create in life and who they want to be, and if marriage and/or motherhood fit that dream, great. And if it doesn’t, great. There are so many ways to be happy! We need a new vision of womanhood and motherhood that makes room for all of our messy, muddled, dare I say, human narratives.

You’ve said this is a book for Gen Z. Can you unpack that?

This is the book I wish I had when I was in my 20s and 30s. When I was veering off the traditional path of “go to college, get a job, climb the career ladder, find a husband and have a baby,” I wish someone had told me that my choices were just as valid. Instead, I thought there was something wrong with me. Why didn’t I want what everyone else wanted? Or at least not at the same time as everyone else? I want to show Gen Z that there are many ways to live a good life. There isn’t one “right” way. There are as many narratives of a good life as there are people. Politicians would like us to believe there are trad wives and then there are childless, cat ladies, but the truth is much more beautiful and complicated. Each and every one of us carries our own story inside of us and I want Gen Z to stop comparing their story to their peers (and to society’s messed up standards) and start believing that every path is valuable and that variety is what makes us human.

Ruthie Ackerman’s writing has been published in Vogue, Glamour, O Magazine, The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Salon, Slate, and Newsweek. She launched the Ignite Writers Collective in 2019 and has since worked with hundreds of writers to publish their own stories. Her client wins include a USA Today bestseller, book deals with Big 5 publishers, representation by buzzy book agents, and essays in prestigious outlets. Ruthie Ackerman has a master’s degree in journalism from New York University and lives in Brooklyn with her family.